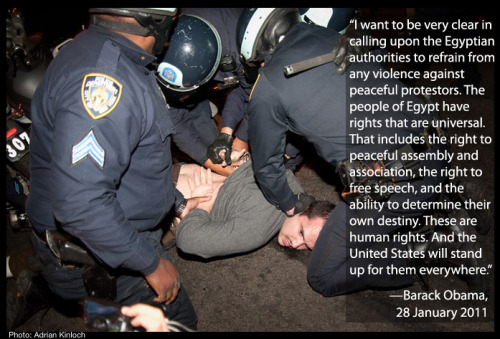

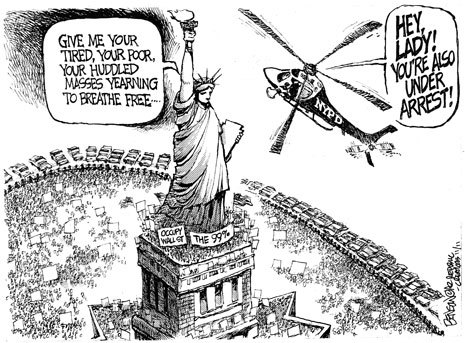

The Occupy Wall Street encampment in Zuccotti Park was many things to many people. For some, it was the dawning of a new age, to others a throwback to an earlier one. Before the mini-society was destroyed by city authorities last week, some looked at it and saw petty crime, pathogens and pathos, while for others it offered a rare glimmer of hope for a future based on economic justice, mutual aid and greater equality.

What activists inside the park saw as the nucleus of a new society, the New York City Police Department saw as a prime target for terrorists, according to a plainclothes policeman. The white surveillance truck at the corner of Liberty Street and Broadway, the many security cameras aimed at the plaza and the massive police response --including dozens of NYPD vehicles -- he and his partner claimed, were not there to police protesters, but to thwart an attack on the park by armed militants.

Just hours before NYPD officers raided Zuccotti Park, rousted the occupiers and destroyed their encampment, I had a run-in with these plainclothesmen and listened as they spun their tale.

In the days since, reports of a terror plot to attack police and military targets in New York City surfaced. If these allegations, as well as those by the plainclothes officers, are actually true, they suggest the NYPD may have put protesters at increased risk of a terrorist attack.

Spy v. Spy

While reporting from the environs around Zuccotti Park, on the encampment’s final day, I spotted two middle-aged gentlemen leaning on metal barricades in front of One Liberty Plaza, the massive office tower that looms over Zuccotti Park and is owned, like the park, by Brookfield Properties.

One sported close-cropped dark hair, wore a nondescript black and gray jacket, dark blue jeans and brown sneakers. The other was clad in a similar uniform: black jacket, lighter blue jeans, but his hair was a steel gray and very distinctive.

These men weren’t there simply to take in the scene. They weren’t day trippers or tourists. They didn’t work in the office buildings around Liberty Plaza or close by on Wall Street. They were, experience told me, on the job.

I’m not sure who noticed who first, but we danced around each other, from the sidewalk on the perimeter of the park to the streets around the plaza for the better part of an hour -- monitoring each other’s movements, stealing glances around corners, alternately pretending not to notice each other and looking away when caught, as if we were playing a juvenile game of spy v. spy.

Finally, they broke the rules. Holding up a personal digital assistant and taking a photo of me without pretense was, in my opinion, unsporting and I called them on it, waving to the gray-haired man as he snapped another shot.

The game was up so the duo, now loitering on Liberty Street, jaywalked over to the park side, moved aside the barricade and confronted me on the sidewalk.

At first, the gray haired photographer did all the talking. He was serious bordering on surly and wanted to know just what I was doing, so I explained I was reporting for AlterNet about the security response to the Occupy Wall Street protests.

Having been repeatedly hassled by officers while covering the policing of the park, I wasn’t shocked by what came next. The talkative one wanted to see my NYPD press credentials and then asked if I was a protester from “inside the park.”

“No, I’m a reporter,” I told him and tried to set him straight that police press credentials don’t have any bearing on whether or not someone is a reporter.

Now it was my turn to serve up some questions. Since they had never bothered to identify themselves as policemen, I asked: “What’s your story…detective?” leaving him a conversational gap to fill in his name and correct me because the odds are, he wasn’t. He declined on both counts. So I asked, “You’re a detective, right?”

“I work for the NYPD,” he replied.

Neither would offer up his name, but I took the opportunity to continue my questioning just the same.

Terror at OWS?

I turned and pointed toward an unmarked police vehicle parked across the street from where we were standing. The truck is white with no markings, save for an NYPD license plate. A 40-foot pole, with a single helix of heavy-gauge electrical cable coiled around it, topped by a video camera, rises from the back of the truck and all day long, that camera is pointed at Zuccotti Park.

Having previously seen officers with jackets bearing the initials TARU – meaning they belong to the Technical Assistance Response Unit, the officers who monitor and videotape protests – enter and exit the vehicle, I asked if it belonged to that unit. “TARU?” the talkative one asked, like he had never heard the term. I repeated it and he shook his head no.

It is NYPD surveillance, right?

It’s not surveillance.

(Now, this was a direct contradiction to what police officer Anthony Torres had told me, on this very same block, just two weeks before, but I kept that information to myself.)

No? Then what kind of vehicle is it?

It’s a white truck.

Yeah, but with a camera on top. If it’s not for surveillance than what is it for?

It’s for the safety of the people in the park.

How does a camera provide safety?

At that, the talkative one meandered through the barricades and into the street, ignoring my question and, I think, trying to get a better look at my notepad. At that, I turned to his partner, who turned out to be the “good cop” of the pair, and I repeated my question to him. He quickly turned talkative and shared his theories.

Think about it, how many people are in this park right now?

Several hundred, maybe more.

You don’t think this could be a soft target for a terrorist attack?

Hold on, terrorists are going to target the park?

He explained that terrorists didn’t care who they killed, so they might well try to wipe out Occupy Wall Street.

If that were true, I asked, why weren’t there similar non-surveillance trucks at events of even higher population density all over the city? As he fumbled, I peppered him with follow-ups, prompting him to change the subject.

He soon went for a favorite bully tactic of New York’s finest, admonishing me that I should really have departmental press credentials.

“No, no, no,” I admonished right back, informing him, again, that those NYPD IDs simply allow some journalists to cross police lines to do crime reporting, but that I was on a public sidewalk, so I needed nothing of the sort.

Then, he took another tack. Hadn’t I heard all the horror stories of crime in Zuccotti Park? I told him I had, but that such an argument hardly helped his case because any crimes there had taken place under the watchful eyes of the NYPD cameras, meaning their surveillance efforts were woefully ineffective in the role he was touting. He countered by saying the protesters in the park didn’t want the help of the police because they had their own security.

But if you see a crime in progress you have to take action, right?

Well, they don’t want us in there…That’s the whole thing.

But, if you see a crime taking place can you just let it go? Don’t you have to intervene?

Of course we do.

“Then what good is that camera?” I said, gesturing to the white non-surveillance truck. He went back to arguing that the camera was simply for the safety of those in the park due to the persistent terrorist threat, to which I responded with an incredulous look and a laugh. He said it was no joke and kept on pressing his point. The white truck, he continued contending, was absolutely vital to police efforts in keeping the park safe from terrorists.

“Really?” I asked, pointing out that a short distance from the truck was a NYPD command post with a camera on its roof, a permanent, stationary camera on a light post, and then there was the Sky Watch surveillance platform, with its five cameras, down the street. “Isn’t it overkill?” I asked.

By this time, the gray-haired “bad cop” had rejoined us on the sidewalk and the two began moving away from me.

Apparently, they had had enough.

As a parting retort, the good cop offered up a variation on the Nuremburg defense. Listen, we don’t give the orders, we just follow them, he said as they moved the barricades and began jaywalking back across Liberty Street.

“Who do these orders come down from?” I called out as they walked off.

“Commissioner Kelly,” he responded.

“Kelly?” I asked again to make sure they had, indeed, blamed New York City’s police commissioner.

“Yeah,” said the “bad cop” and then they were gone.

(The NYPD failed to respond to AlterNet’s request for further clarification on Kelly’s role as the architect of the security response to the Occupy Wall Street protests.)

The next day when I arrived on the scene, the protest in Zuccotti Park had indeed been wiped out, not by terrorists, but by the NYPD. Empty, except for uniformed park security personnel and later police, the park was still under the watchful eye of the white surveillance van and surrounded by dozens of police vehicles as it had been for weeks.

By the afternoon, a man wearing an NYPD TARU jacket was standing on the roof of the white truck, wielding a handheld video camera while, all day long, men wearing similarly monogrammed jackets and shirts entered and exited the vehicle. Inside, sometimes as many as six members of the unit, surrounded by multiple monitors streaming footage, digital video recorders storing it away and even a somewhat archaic fax machine, monitored the scene.

Later in the day, I noticed the “good cop” standing in the middle of Liberty Street, talking with other “special” policemen – not the rank-and-file officers in riot helmets who stood guard over the locked-down park throughout the day. He was later joined by his gray-haired partner.

From behind the police cordon, I tried to get their attention so that I could follow up, but I could never quite get them to acknowledge me. Now, it seemed, they were far less concerned about my reporting and were in a much lighter mood than before the encampment was destroyed. In fact, I noted, they were joking around and laughing hard.

Cause for Alarm

Less than a week after the NYPD raid on Zuccotti Park, Commissioner Kelly would announce that, after tracking him for two years, the NYPD had arrested a Manhattan man who had reportedly sought to build homemade bombs in order to carry out terrorist attacks. At a Sunday night press conference, Kelly alleged that 27-year-old Jose Pimentel sought to attack police cars in New York City, as well as post offices and U.S. troops returning from the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. The NYPD failed to respond to AlterNet’s questions about why it surrounded Zuccotti Park with a profligate number of police vehicles when these were, according to Kelly, known to be precisely the targets of a man who wished to become “a martyr in the name of jihad."

Whether Jose Pimentel’s case turns out to be substantive or one of a number of generally inept terrorist plots – including those of the Liberty City Seven, the Fort Dix Six, the Detroit Ummah Conspiracy and the Newburgh Four – that are often fueled, in part, by law enforcement agencies remains to be seen.

Regardless, the latest alleged plot and recent NYPD statements concerning security camera surveillance raise serious questions about the actions of the department and its frequent resort to using the cover story of anti-terrorism to cloak unrelated spy tactics and others matter they would rather not discuss.

If the NYPD were more forthcoming and honest, perhaps their words and actions wouldn’t suggest that the department, specifically Commissioner Ray Kelly, took steps to make protesters in Zuccotti Park more likely victims of terrorist violence.

Now that the encampment at Zuccotti Park is gone, it remains to be seen whether the surveillance effort to protect it from terrorists will endure.

From Occupy Davis

From Occupy Davis